& F4 Collective

The Unknown A4 wall text

Like many museums, Auckland Museum is dedicated to collecting, preserving and sharing the past through its objects, texts and photographs. Within the histories these things embody, great events and deeds are memorialised and when it comes to people, photographs play a very special role. For here is a truly remarkable likeness of the person captured as if in a magic mirror. The person in the image and the material object that is the print are locked together for as long as the material lasts, their fates indissolubly entwined.

“Bereft of specificity; name, place or date, we are nonetheless cognisant of the past through the existence of these images, traces left on glass, disassociated from their own familial ties”. (F4)

Unidentified opaltype portrait. Hand painted highlights.

The Unknown Woman, is a photographic portrait that has been almost entirely eliminated by hand painting, the only part of her image that remains steadfastly photographic is her ear.

Unknown Opalotypes

Printed on opaque milk glass, opalotypes, which emerged in the 1860s,present a portrait on a white ground. The positive image was printed from a negative after a light-sensitive coating was applied to the white glass surface.

To further enhance the image, painted details were often added to colour the sitter’s garments. In some cases the latent image is almost completely obscured, or painted out.

Glass opalotypes are fragile, and it is not uncommon to find them framed or adhered to a backing board.

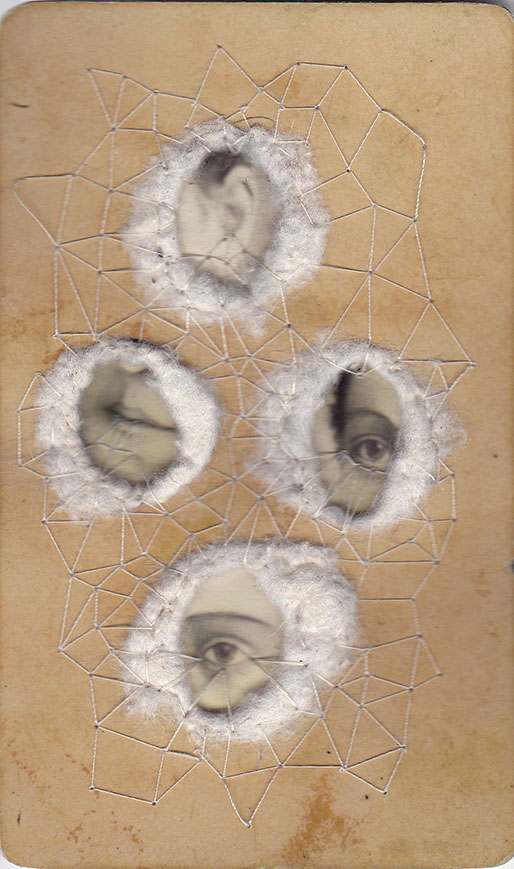

F4 has responded to visual clues evident within the photographs, in The Unknown the images have been selected from the museum archives, not only for their unknown histories but also for their physical qualities.

Using collage, montage and digital alteration F4 are insinuating relationships between their work and the chosen photographs, often combined to make a tableau , the images are arranged in a manner that hints at an encounter, thus emphasising and extending the disconcerting nature of their anonymity.

Gerald E Jones Cyanotype 1880 – 1963

Unknown Cyanotype

Characterised by their unusual colouring, these Prussian-blue prints are derived from a solution of iron salts that allowed the cyan colour to emerge when exposed to light through a contact negative. The deep blues of a cyanotype present a distinctive view of the world and a tantalising alternative to black and white tones.

This 19th century process was used for many decades to reproduce architectural drawings, commonly known as blueprints. The colour embedded in the paper’s fibres with no photographic surface as such, leaving a very matte finish. Paper could vary from home-made to commercial.

Cyanotypes were often made as experiments as the image will print out from light alone, allowing for the creation of sun prints and photograms which develop in front of the viewer

Working with the Auckland War Memorial Museum’s large photographic collection has been intoxicating. The breadth of unknown portraits is staggering, yet despite their loss of identity – they retain aspects of their provenance, their image remains as an effigy, they commune with the present through a multitude of signifiers, their name and personal narrative may be lost to us but their voice is not quieted, they speak to those who take the time to listen and their stories are in equal measure wondrous and mysterious.

Unknown Portraits from the Kelsey, H. H. Photographic Collection 1907 – 1920 – Silver gelatine, Support Glass. Click on image to view individually.

Unknown Glass plate negative

Starting with the collodion wet plate and moving onto the gelatin dry plate, negatives on glass could render more detail than most film variants due to their larger size. Referred to as quarter, half and full-plate sizes, the original 19th century plates were hand-cut to fit a camera and coated during use. With the invention of dry plates it became possible to carry several plates in a magazine.

Glass plates were usually contact printed to produce an image on paper of the same size. The size and form of a glass plate allowed for fine detail without curvature.

The negatives were often annotated, the writing appearing as white when printed in positive.

Curator of Pictorial, Shaun Higgins began to notice the reappearance of one person in the AWMM’s Kelsey Photographic Collection. This unknown man appears again and again, he poses wearing different guises and in different tableau, as well as in a ‘candid’ image hiking in the snow.

Many of Kelsey’s photographs are landscapes, but this set of images are whimsical, clearly set up in a studio they have been planned and executed with care. The image of the man in the rain has even been augmented – the glass plate appears to have been deliberately spattered with a dark inky substance that has been wiped away very carefully from over the man’s face so that he is clearly visible.

Staged photography formed a vital part in early photographic production, ironically often as a strategy for achieving higher degrees of realism due to the awkward nature of the technology.

F4: Moana. 2007 Family portrait pictorially referencing the photograph of ‘Taonui Hikaka; Leading Ngati Maniapoto chiefs including Rewi Maniapoto’ c1881(?). Photograph by Alfred Burton. Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hakena, University of Otago, New Zealand.

Kelsey Collection, an unknown man wearing a Korowai.

F4 studio tableau’s 2010, formal portraits taken in our studio at the ISCP in New York and constructed into narrative scenes in photoshop, allowing different sequences of events to be orchestrated. Click on image to view individually.

“It is possible to conceive of photographs as objects for the saviour of self, as photography presumes in some part that we may all lose either memory or identity or both.”(F4)

It is interesting to note that the portraits that attracted us were those that isolated the person in ‘no-space’ rather than real life, each portrait is freed from the temporal through enacting a pose. Time is irrelevant in these portraits, though the photographer opened the lens for a fragment of time last century, they retain their sense of self-possession, the blank space becomes a metaphorical place of performance and as we watch the actor entrances us. Suddenly we are no longer in the presence of an unknown person, the locked space they occupy has become saturated with meaning, drawing us visually and emotionally into the portrait, a space open to the imagination.

Unknown photographer (ca. 1860) [Portrait, female] PH-TECH-370-7 Ambrotype (90 x 80 mm)

Unknown Ambrotypes

Introduced in the mid-1850s, ambrotypes are underexposed collodion wet plate glass negatives that have a black backing. The backing was either black enamel or black velvet. It created a positive image from the negative, the clear shadows turning black and the remaining opaque area becoming highlights.

The fragile surface was then placed behind additional glass in a case for protection. They were commonly presented in Morocco or Union cases.

When you look into the frame of an anonymous image, you gaze into the sublime, unimaginable expanse of the unknowable past. There is a bittersweet sense of loss that becomes inextricably associated with the physical things that are the printed objects in front of you. You become more aware of the pathos and beauty of the objects; their objective reality competes with the family or persons that you see within. You start to see the glass, tin, copper, paper and velvet. You see that they are etched by patina, chipped, faded or oxidised. You see the fragile provenance of the last vestige of the unfathomable number of moments, which was once a life. You see that only one of these moments remains, here captured from the entire life of an unknown person and embedded in this decaying object.

A page from an album of visiting cards. You would leave your photograph, as a calling card when you wanted to arrange to visit someone. Albums of filled with small unidentified portraits, the cards also collected by someone unknown as a memoir to social transaction and etiquette.

Unknown Carte de visite

From the 1860s these small prints formed part of a visitation ritual. A carte-de-visite, or visiting card, was easy to obtain, being printable and inexpensive compared to a cased photograph. A visitor could present their portrait card which would be later placed into an album.

These albums not only document occasional visitors to a household but also families.

Cartes-de-visite are small albumen silver prints mounted on card, often with a studio name below. When the cards were slotted into the albums, messages written on the verso became hidden. A century or more later these messages were once again revealed whenever the cartes were removed from the albums.

Aspirations contained within a public image of oneself – opening the sitter up to intense scrutiny and fascination driven by a recognition of otherness and similarity. If the temporal is conceived of as a web of interconnecting moments, photographs become inter-subjective fragments. The photographic object captures the fluid precession of time, enabling us to know the world in a manner not possible prior to its invention. Photography chronicles lived experience, whether constructed or documented, it is cherished for its resistance to the virus of dematerialisation.

F4: Salvaged page from my mothers photograph album.

F4 has an obsession with arrangement, as most photographers (and Museums) do. More now than ever before, photography functions as the most ubiquitous tool by which we identify, validate and construct ourselves, to the point where lived experience is in some way simply not legitimate if not captured.

Victorian’s too were entranced by the democratising power of photography, they craved in equal measure the vestigial assurance of the imprisoned moment – incessantly rearranging cultural clues so that we might know again, see anew and attest to their existence. Yet the fastenings of memory have worked loose under the prying fingers of an unremitting future.

F4: The whisperer. The Unknown 2016

How then can we re-fasten memory?